These Articles Are Reproduced With Special Permission From Archeological Diggings Magazine

For More Information And A Subscription, Please Visit www.DiggingsOnline.Com

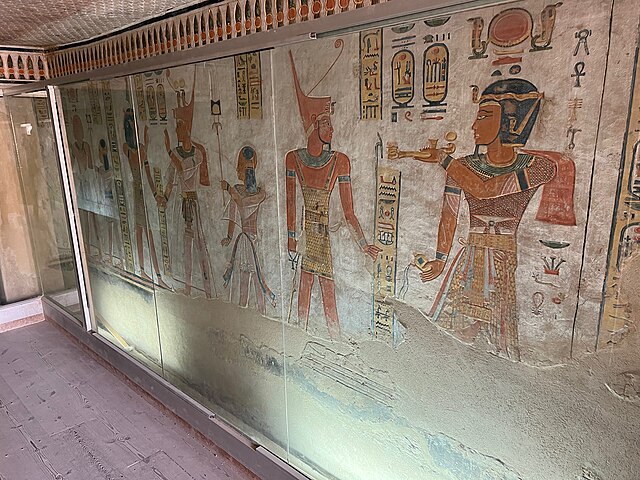

Tomb 55

Tomb 55 in the Valley of the Kings has been a bit of a mystery ever since it was discovered in 1907. The tomb had been badly damaged by flood water and its sole occupant was a wooden sarcophagus lying on the floor, its lid split in two by a piece of rock that had fallen from the ceiling.

Nevertheless, it was clear that the sarcophagus had belonged to someone quite important, for it was richly decorated with gold and lapis lazuli. The eager excavators at first identified it as the sarcophagus of Akhenaton, the heretic pharaoh, for the cartouche had been carefully chiseled out and the golden face of the occupant had been ripped off. When they turned to the mummy, however, they were faced with a surprise.

When it comes to royalty, the ancient Egyptians conformed to certain conventions. Men – pharaohs and such-like – had their arms crossed on their chests; women, on the other hand, had one hand straight down by their side, and the other was laid with the hand positioned neatly between the breasts. These stances were reflected in the mummiform sarcophagus, and the sarcophagus in question was clearly male.

The mummy inside, however, was wrapped up in the female position. The surprised excavators hastily changed their minds and identified the unknown corpse with one of the female members of the Amarna period. It couldn’t be Nefertiti, for her tomb was known, but it might be Akhenaton’s mother, and so it was announced to the world.

A few months later, however, the mummy was examined by anatomical experts, who conclusively decided that the body was that of a young man! Opinion swung drastically once again. It could not be the body of Akhenaton, for it was too young; it was possible, then, that it might be the body of one of his younger brothers and current thought is that it might be the body of Smenkare. Indeed, in view of the somewhat ambivalent relationship between Akhenaton and Smenkare, which may have been a homosexual one, it has been suggested that Smenkare was buried in a female pose either by a grieving lover or as an expression of disgust by a group of strait-laced mummifiers. (This last suggestion does not seem likely to me, for there were various religious ceremonies to be conducted before the mummy was laid to rest and the possibility of such a nefarious action escaping detection seems remote.)

The lid of the sarcophagus has long lain in the Amarna section of the Cairo Museum, but I was unaware that the bottom part was anywhere other than in the museum basement. In fact, neither were the museum authorities. In 1931 they suddenly woke up to the fact that the sarcophagus – or rather, the fragments that had survived – was missing and no one knows how it turned up a few yeas ago in a private collection owned by a Swiss national. This gentleman left his collection to the Staatliche Sammlung Aegyptischer Kunst in Munich, the director of which was somewhat startled to find what he had been given.

Naturally, he informed the Cairo authorities of his discovery and was slightly put out to receive a prompt demand for the return of the object, for he had just spent $90,000 on necessary conservation of the bits of gold foil and coloured glass hieroglyphs inlaid into bits of wood which is all that survives of the lower half of the sarcophagus. He suggested that the Cairo Museum might care to reimburse him for this work, but hardly surprisingly the Egyptians were less keen and after considerable negotiating the Munich museum has agreed to foot the bill and return the objects to Egypt as a gesture of good will.

August 2001